Choosing the families

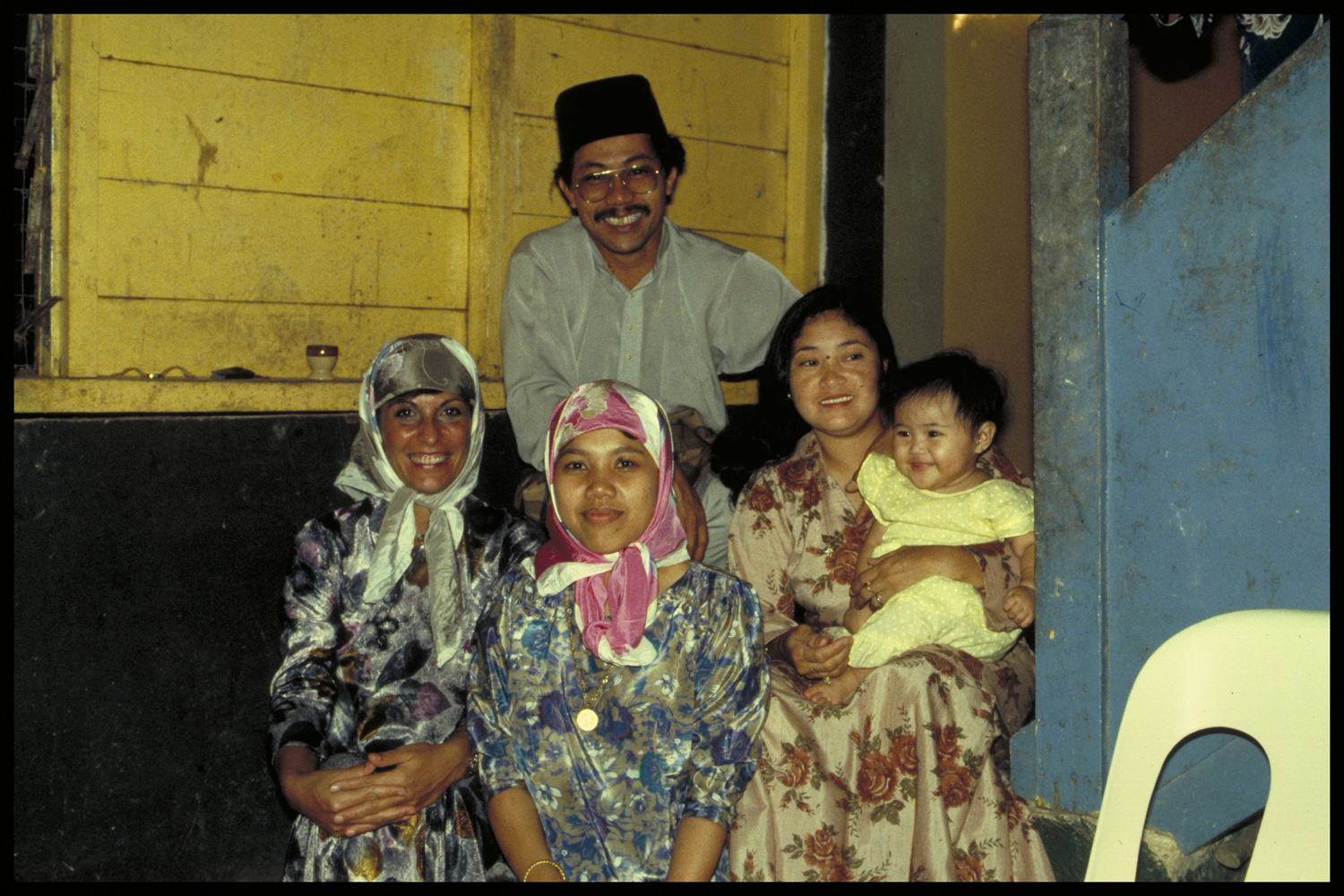

The families I visited to present Humanity to Humanity, were chosen from detailed statistical profiles and accurately reflect the characteristics of each country. If the majority of a country’s population is rural, the family chosen to represent it is rural. The family earns the average national income and has the number of children that corresponds to the national average. The family’s home also had to be representative of the country’s architecture and the predominant standard of living. For example, if the majority live far from the main roads, I would walk to find my family.

Other factors also influence life-styles: access to electricity, to safe and piped water and to roads. A country’s major problems must also be taken into consideration: deforestation, over- population, migration to the cities, the inequalities of the social classes. Looking at a map is very different when you try to imagine who lives where, and what the climate and geography are like. Life varies in high altitudes, on the seashore, in the desert, in countries with monsoons, in villages, in cities of 10,000, 100,000, or one million inhabitants. And the choice of family is made even more difficult when half the population is rural and the other half is urban.

Data tells a lot about a country and it’s inhabitants’ living conditions. When I find myself in a country where, for instance, there are no statistics available on how many sixteen-year-olds are in school, at work, or unemployed, because research has not been done or compiled, I can only ask myself: What are they doing for their young people?

When all the information I have gathered takes me to a particular region, the personnel of the United Nations establishes the contacts with local professionals, working at the grass-roots level. Group sessions are often required to define the family’s main features and to locate someone who knows the community intimately enough to knock on a family’s door and introduce me. That is how I discovered the incredible work women’s organizations are doing. Their work is often voluntary or very poorly paid, the time and energy I have seen them give to their communities has more than once amazed me. It is through these people that initial contact with a family is made possible. If the person, I am with at the time comes to knock on doors, is someone whom everyone trusts, then I benefit more readily from such trust. This is a crucial element, since in general, families are not notified of my coming. Another is the ability of the interpreters to adapt with me to the daily life of my family and gain their confidence. Even if they are in their own country they often have more difficulty then I have.

We visit three, four, five families and I choose one. Here I am! I put down my bags. One day I follow the women, another day I follow the man and the next I follow the children. I put all of these days into one. Sometimes I take two or three weeks per country to accomplish my research, I spend four days in the family.

Hospitality

I tried five days but, I felt that it was too much. A simple feeling. Then it is with the Bedouins, the desert people of the Middle-East, that for them hospitality lasts three days. They say that after that, the guest is like a cheese, its start smelling! One must know when to arrive and when to leave.

I must have seemed too demanding to those who were kind enough to help me in my search. I often insisted that the family have one more or one less child, a larger or smaller house, or that the heads of the household have different occupations, in order to correspond adequately to the ideal statistical profile. In that respect, I tried to depict the daily life so that readers who are part of the mainstream in their own country can reflect: if I had been born there, that is how I would live.

To communicate with Humanity

It is not necessary to know all the languages of the world to speak to each other. Communications with my families were often a question of a glance and of the interpretation of their body language and heart. In fact some of the most difficult departure were from people with whom there had been mostly a silent sharing. No words were necessary.

Imagine if we were all dressed from head to toe and we would have only our eyes to communicate. What we put in our look? Anger? Hatred? Vengeance? Contempt? Or would we put love? Compassion or tenderness?

To communicate with Humanity it is your eyes that you must dress?